Media literacy in a digital world

Our Director of Evidence and Engagement, Dr Emma Stone shares her thoughts on media literacy, and how it links to digital inclusion.

Bamboozled

March 16th was International Panda Day. I’m aged 13, or 43, or 73. I really like pandas. I decide to post a picture of a wild panda eating bamboo.

In 2025, this means I’ve probably: Used a smartphone or tablet, which is connected to WiFi, or uses mobile data, gone through my security settings, opened my web browser, typed in what I’m looking for, found lots of (cute) images, clicked on my favourite, then clicked on the ‘share’ icon, chosen how I want to share it, who I want to share it with, and shared it. Do I spot it may be subject to copyright? Do I wonder whether it is real or AI-generated? Do I care? Uh oh. Now I’m reading about people eating bamboo… and finding bamboo recipes…

The level of digital access, skills and understanding that we need to engage online keeps on rising. Even my simple, no-threat story takes a pretty complex combination of kit, practical and safety skills, and the skills to evaluate what I find, whether to trust it, use it, share it. I type: ‘Are pandas endangered?’ An AI Overview pops up without me asking. Do I know what this is? Do I trust it? Do I spot that I can click on links to check sources? Do I check?

Bamboozle can mean to confuse. It can also mean to deceive or dupe. It turns out that most of us are easier to bamboozle than we’d like to believe.

How digitally and media literate are we?

Ofcom, the communications industry regulator, has had media literacy duties for 20 years, including public education, and research. Ofcom’s annual reports on media use and attitudes are an invaluable source on digital and media literacy. Some insights from the 2024 report:

- Misinformation and disinformation is a major concern:

- 45% of adult internet users claim to have seen a deliberately untrue or misleading story on social media in the past year; 14% acted in ways which risked spreading it further

- 15% of social media news users say they rarely or never consider the truthfulness or accuracy of the news they see on social media.

- There’s a gap between confidence and competency:

- 17% of social media users felt confident they could identify whether online content was true, but weren’t able to recognise the fake profile presented

- 37% of search engine users felt confident to recognise advertising online, but were not able to recognise advertising in reality.

- A significant minority are in the dark about how companies use their personal data:

- One in ten internet users are unaware or unsure of any of the many methods used by companies to collect personal information

- One in five are unaware of the use of algorithms to tailor what people see.

- Only 37% of AI-aware adults ‘ever’ consider if something written online might be AI-generated. Only 27% of AI-aware adults were confident they could identify AI content (more likely among those using AI themselves, 16-34 year olds, and men).

The consequences of low digital media literacy scare me. Children, adults, and communities are experiencing harm and hurt - financial, emotional, psychological. Many are feeling left behind, fearful, inadequate, overwhelmed. Trust is falling. Confidence is misplaced. Civil society, democracy, cohesion, and security - all are threatened by new era online harms. We should expect more and better protection from tech platforms, social media providers, public broadcast media, governments, and regulators. In the UK, we have new legislation in the Online Safety Act and the Media Act; will it be enforced in a way that improves our lives and experiences online? Meanwhile, we can act too, and help to build digital media literacy.

How are media literacy and digital inclusion related?

Digital media literacy is about how we understand, question, navigate, and manage the online world. This is essential for us to benefit from being online, be aware of, and avoid risks and harms. It is part and parcel of digital inclusion.

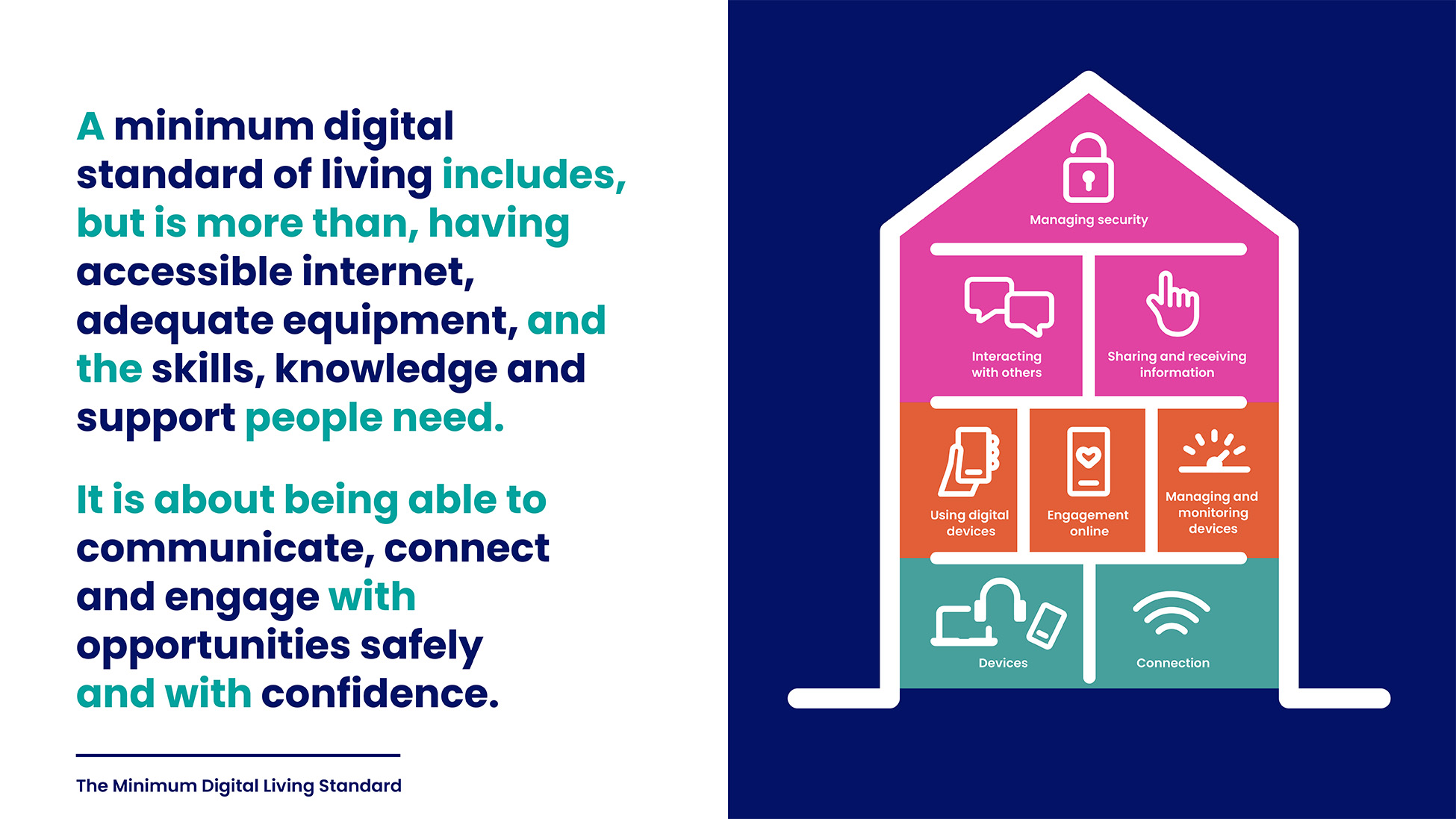

When members of the public deliberated what’s needed to be digitally included, they agreed that households need a combination of suitable kit and connectivity, and practical skills, and critical thinking skills. All are needed, in combination, for a Minimum Digital Living Standard. Last year, face-to-face survey research with 1,582 households with children found that:

- A quarter (27%) of households with children have parents missing the critical thinking skills which members of the public said were essential for household digital inclusion.

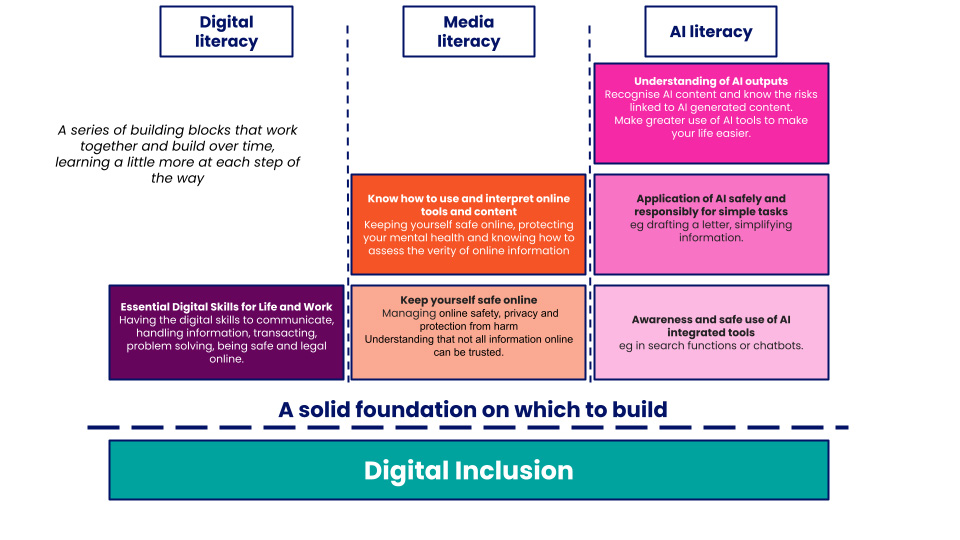

For Good Things Foundation, our research with community partners in the National Digital Inclusion Network to explore how to develop basic AI literacy among people with low digital skills confirmed the importance of addressing digital inclusion first. Digital inclusion is the solid foundation you need, upon which you can then layer and build higher levels of digital, media, and AI literacy. And, following the MDLS, that solid foundation should include basic elements which cut across literacy silos.

For us, media literacy is one of several literacies, and numeracy, which we all need to navigate the online world. Yes, different literacies have distinctive elements, but when it comes to everyday essentials for engaging online - for social, economic, cultural, and civic participation - we need to draw from different literacies. We need to start with people, with everyday life, with what matters most.

We need to get digital inclusion - and digital, media, and AI literacy - right from the start. This means rethinking literacy and numeracy in an online world - and supporting children, teachers, and parents in schools and in their communities.

We need to rethink lifelong learning in communities - especially for adults who face digital barriers (whether access, skills, confidence, support - or a combination of all these), and who may have had poor past experiences of education or training. This means creative, cross-cutting, and person-centred approaches which reflect people’s own lives and interests, and enable people to find agency, confidence, and critical thinking to benefit from digital.

Taking action. Calling for action.

With Ofcom’s support, we’ve reviewed the bite-sized topics on ‘Learn My Way’ (our online learning platform designed for use in libraries and community learning settings) against Ofcom’s Media Literacy Outcomes Framework. Taking advice from community practitioners, we’ve created new content and augmented existing content, with more planned. We hope this will make it easier for people working in community hubs to support others to build basic elements of digital media literacy into their digital inclusion journey.

We’re also calling for systemic change in how digital inclusion and skills are conceptualised, supported, and funded. A recurring theme in research commissioned or curated by Ofcom and by the previous government is the fragmented, piecemeal landscape of provision. But what about the fragmented, piecemeal landscape of policy making?

Currently, there is no clear ownership of the Essential Digital Skills Framework - a framework which also needs to stay relevant and reflect what the public feels is important (MDLS). In England, the Essential Digital Skills entitlement, qualifications and adult education funding are failing disadvantaged adults, and failing the community organisations and libraries who support them. Ministerial and policy responsibilities are confusing, and seem to holding back real change. Adult skills is with the Department for Education; media literacy is with Ofcom; digital inclusion is with the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology; and skills is also a devolved policy area, largely delivered through devolved funding streams. This is a fragmented policy and funding landscape which feels a long way from where we need to be.

We’ve called for action in our responses to the Government’s Digital Inclusion Action Plan First Steps, in our evidence to the House of Lords Communications and Digital Committee’s Inquiry into Media Literacy (written and oral - you can watch here), and the Department for Education’s Curriculum and Assessment Review. Positively, the Government's Digital Inclusion Action Plan First Steps recognises the need for cross-government sponsorship. We are now looking for decisive next steps to clarify ownership and drive delivery of a cross-government approach to digital inclusion and skills. Without this, we’ll be left feeling confused, frustrated … bamboozled.

.jpg)