Tackling Data Poverty: Innovation and collaboration

This report, the latest from the Data Poverty Lab, explores the role of innovation - both technological and systemic - in tackling data poverty. By Dr Sarah Knowles with Dr Emma Stone.

Below we summarise the research and key learnings. For the full report, please download the PDF version linked in the Downloads section. Or, you can watch our webinar launching the latest Data Poverty Lab research on-demand below.

Forewordback to top

We now live in a digital-by-default world. Across health, education, commerce, work, and leisure, access to services and opportunities is mediated online. In 2025, we stand on the brink of another transformation, as agentic and generative AI promise to accelerate progress for those on the right side of the divide, while leaving others even further behind.

As the guardians of .UK, Nominet operates the national domain name registry on which millions of individuals, organisations, and businesses rely each day. As a public benefit company, our mission is to deliver positive societal impact - shaping a safer, more inclusive, and better-connected digital future.

The widening gap between the digitally connected and the digitally excluded galvanised our work with Good Things Foundation, and led to a shared commitment to address data poverty. Through the Data Poverty Lab, we laid the groundwork for some of the UK’s most ambitious and imaginative responses to this issue. Together with leadership from telecoms industry partners, efforts such as the founding of the National Databank, and reimagining models such as zero-rating of online public services, have helped hundreds of thousands of people gain temporary access to the digital world - a lifeline in times of need.

This report, the latest from the Data Poverty Lab, explores the role of innovation - both technological and systemic - in tackling data poverty. It highlights the untapped levers for change that lie within our policy frameworks, our regulatory structures, and digital infrastructure. It invites us to question our own responses to the consequences of data poverty, and consider our role in shaping the society we want, and the internet we want.

There is nothing inevitable about data poverty or digital exclusion. But confronting it requires bold thinking, cross-sector collaboration, and a collective willingness to reimagine how connectivity is distributed in the UK. This report is a step in that direction. We hope it informs, provokes, and - most importantly - inspires action.

Chris Ashworth OBE,

Head of Social Impact, Nominet

Executive Summaryback to top

Data poverty is when an individual or household cannot afford sufficient, secure connectivity to meet their essential needs.

Around 1.9m households with a mobile phone, and 1.6m households with fixed broadband, struggle to afford their service (Ofcom 2025)

Ideas behind today’s innovations

“Could there be a foodbank, but for data connectivity?”

“Could a single donated SIM expand into a network for several users?”

“Could people access a joined up free WiFi network with one login?”

“Could we send an internet connection across a neighbourhood?”

“Could we provide a broadband offer for people receiving benefits?”

Innovation

The last five years has been a period of innovation and collaboration to tackle data poverty:

- The National Databank and Jangala Get Boxes show how collaboration - commercial SIM donation and third sector delivery - can provide free connectivity to people in most need.

- Initiatives such as Rochdale Mesh and WBA OpenRoaming have shown how safer, easier ways to access free WiFi can be provided in places and communities.

- Improved social tariffs have been developed by market leaders with the regulator and government, making connectivity more affordable for some households receiving benefits.

- Place-based leaders have catalysed collaboration and innovation, finding resourceful ways to tailor and promote solutions to places and communities.

- Calls to make internet access an essential utility, or to ‘zero-rate’ essential public services (so poverty isn’t a barrier to use) have grown as services become digital-first.

Limitations

Challenges that limit today’s innovations from being more impactful are:

- Confusion over what is available, to whom, and for how long - confusion for people experiencing data poverty, and for those at the frontline of providing help or signposting.

- Barriers to access - with the burden of finding and using solutions falling to individuals, families, or over-stretched community, voluntary, and public sector services.

- Funding models that rely heavily on commercial and third sector collaboration, with little central government investment, making impact harder to achieve and sustain.

- Evaluation gaps - so stakeholders, including government, struggle to assess what works, where, for whom, and how - limiting further investment and policy development.

Opportunities

The UK Government’s Digital Inclusion Action Plan: First Steps is a window of opportunity to build on first wave innovations, and make them more impactful, sustainable, and systemic.

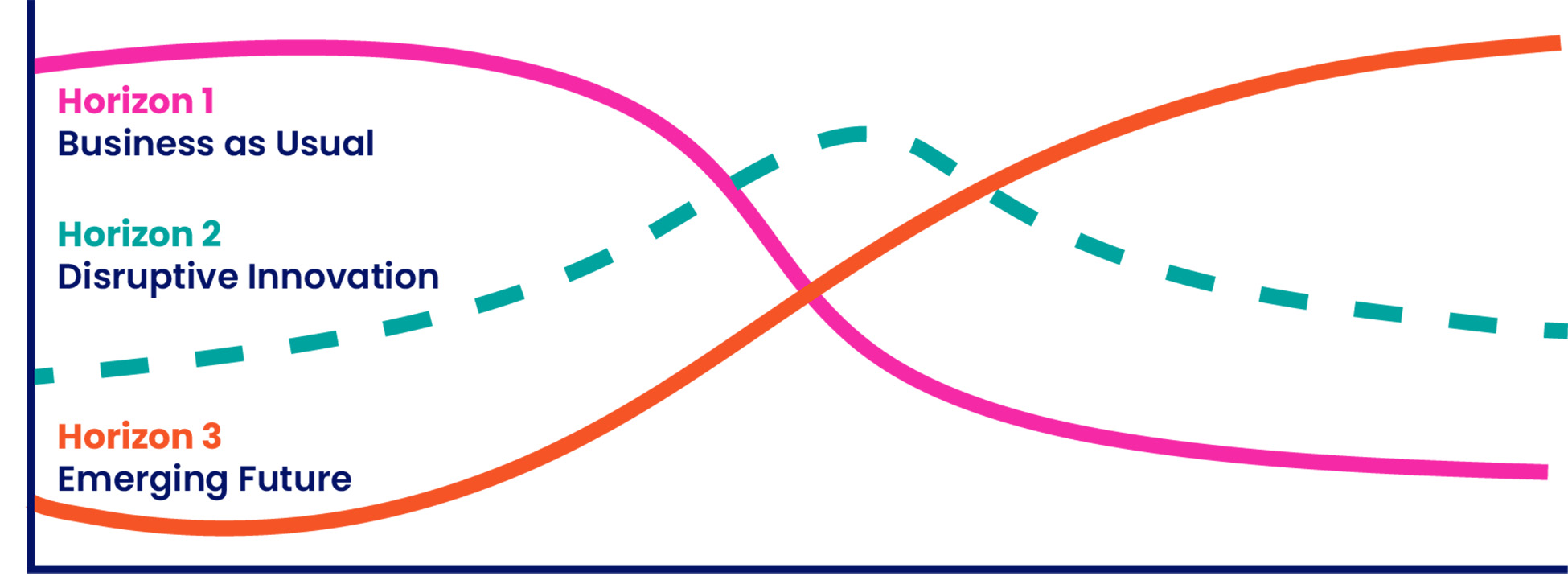

Inspired by ‘Three Horizons’ thinking, we see exciting opportunities for incremental change (‘Horizon Two Plus’), for more radical change (‘Horizon Three’), and for more strategic integration of a range of data poverty solutions to meet diverse needs.

Horizon Two Plus

- Government recognition (central to local) that internet connectivity is essential, requiring better protections and safety nets to prevent data poverty and mitigate its effects.

- Government recognition (central to local) that publicly funded support is needed, as well as sustained contributions from the telecoms industry, civil society, and consumers.

- Strategic integration of different solutions with clearer signposting in national government and place-based approaches to tackling data poverty.

- Reform of affordability support - social tariffs - to be more consistent, less burdensome for people to find and use, and more flexible to meet household needs.

- Reform of crisis support - National Databank - to be sustained where alternatives are not possible, and integrated into local services with government and industry support.

- Government-industry exploration into zero-rating for online public services, and the costs and benefits for data poverty of solutions like OpenRoaming or mesh networks.

Towards Horizon Three

- What if the Government set up a ‘Connected Homes Discount’ scheme - a voucher or payment for eligible households to use with their provider and product of choice?

- What if every organisation with a touchpoint with citizens in crisis, and a requirement for customers to use their services online, embedded the National Databank in their offer?

- What if NHS WiFi, GovWiFi, Eduroam and other WiFi networks joined to create a super federated network across the UK, providing safe, seamless WiFi access for all?

- What if Ofcom mandated a basic (broadband) connectivity package for all customers, improving customer protection and preventing disconnection?

- What if a new public domain was created, with no data charges to people using it, so people could safely and freely access public services and educational content online?

About this paperback to top

The research informing this paper was led by Dr Sarah Knowles, Data Poverty Lab Research Associate. Building on previous Data Poverty Lab reports, the starting point for this research was to take stock of existing solutions, and consider how these might be improved - for greater impact in people’s lives, and to lead to more sustainable, systemic change. At a time when the UK government has prioritised digital inclusion, recognising the need to tackle data and device poverty as one of four focus areas in its Digital Inclusion Action Plan, we hope this paper will spark ideas, debate and action.

The research comprised:

- 22 in-depth interviews with people active in addressing or understanding data poverty, from commercial, public and voluntary sectors, at local and national levels.

- Additional meetings with first wave innovators nationally, and local delivery partners (such as people who set up and run local databanks)

- Engagement with over 40 members of the Digital Inclusion Alliance Wales Network to get feedback on suggested improvements

- Engagement with APLE Collective (Addressing Poverty through Lived Experience) to hear their views as people with lived experience of data poverty

- Reviewing over 40 written documents, including research and policy papers, position statements, internal and public evaluations, and past Data Poverty Lab reports.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the people who generously shared their knowledge to inform this paper. Being able to tap into expertise from the telecommunications industry, regulator, local government and combined authorities, voluntary and community sector, researchers, people with lived experience of data poverty, and previous Data Poverty Lab Fellows and co-authors has been invaluable. The analysis and ideas presented do not necessarily reflect their views.

About the Data Poverty Lab

The Data Poverty Lab is a collaboration between Good Things Foundation and Nominet. Set up in 2021, it is delivering a programme of work to find sustainable solutions to data poverty – the challenge of not being able to afford enough mobile and broadband data. Through Data Poverty Lab fellowships, learning from people with lived experience, thought leadership and convening, we are exploring future-facing solutions. (More information on Data Poverty Lab research to date is in the box below). Inspired by the Data Poverty Lab to be bolder in exploring, catalysing, and striving for systemic change on digital inclusion, Good Things Foundation is now extending this approach to explore other areas of digital inequalities through a new ‘What Works? Co-Lab’. So this Data Poverty Lab 2025 report is also the first ‘What Works? Co-Lab’ report, and reflects a continuing and shared commitment to action, evidence, ideas, and collaboration.

Data Poverty Lab research

Towards Solving Data Poverty (Stone 2022)

CHESS: Co-defining what counts as a ‘good’ solution to data poverty (McGrath 2022)

Scaling solutions to data poverty in the UK (Dixon 2022)

Internet Access: Essential Utility or Human Right? (Nathaniel-Ayodele 2023)

Addressing data poverty for care experienced young people (Parry & Elliott 2023)

Supporting people with data connectivity (Good Things Foundation with People Know How)

Part 1: The Bigger Pictureback to top

1.1 What is data povertyback to top

Data poverty is when an individual or household cannot afford sufficient, secure connectivity to meet their essential needs. The root cause of data poverty is poverty; but it is also shaped by availability and reliability of connectivity, and access to local support and provision.

“The impacts of data poverty widen existing inequalities and perpetuate deprivation by limiting access to opportunities.” (Lucas et al 2020)

There is a clear link between poverty and being offline, with people who are unemployed or earning less being more likely to be offline.

Data poverty in 2025

Ofcom’s Communications Affordability Tracker (Ofcom 2025) estimates that:

- 7% of UK households with a mobile phone struggled to afford their service in the last month (around 1.9m households)

- 7% of UK households with fixed broadband struggled to afford their service in the last month (around 1.6m households)

- 55% of households finding it difficult to afford any of their communications services also had difficulty affording other essentials, like food or energy.

Data poverty and digital exclusion can trap people in poverty or tip them into deep poverty (APLE Collective 2023). People struggling financially sometimes sacrifice other essentials to pay for connectivity (MDLS 2024). Research by the Department for Work and Pensions (2024) finds evidence of this in some of society’s most vulnerable groups.

Groups most likely to be reducing costs in other areas of their life so they can continue to afford broadband internet or mobile data are: People receiving Universal Credit (30%); Job Seekers Allowance (28%); Disability Living Allowance for Children (24%); Personal Independence Payment (21%); People who had been declared homeless at some point (29%); People of non-white ethnicity (27%); People with both physical and mental disabilities (23%); People who were currently unemployed (26%); People who did not have English as a first language (28%); People without formal qualifications (15%); Full-time carers (23%); Students (26%); Retired people (10%) (DWP 2024).

Data poverty can mean exclusion from being online at all; exclusion from the financial (and other) benefits of being online; worsening financial challenges by prioritising connectivity. Data poverty can be severe (unable to afford any connectivity) or intermittent (unable to afford sufficient connectivity and regularly losing access). By contrast, people using online access to shop for better deals, monitor spending, and manage their money are reaping the benefits (Lloyds UK Consumer Digital Index 2024).

“They're trying to keep on top of bills and finances and so paying for a broadband package becomes another sort of burden, they can be getting into financial difficulty as a result. So they're connected but I would say they're very much still experiencing digital poverty because they aren't able to sustainably maintain that connectivity.” - P9

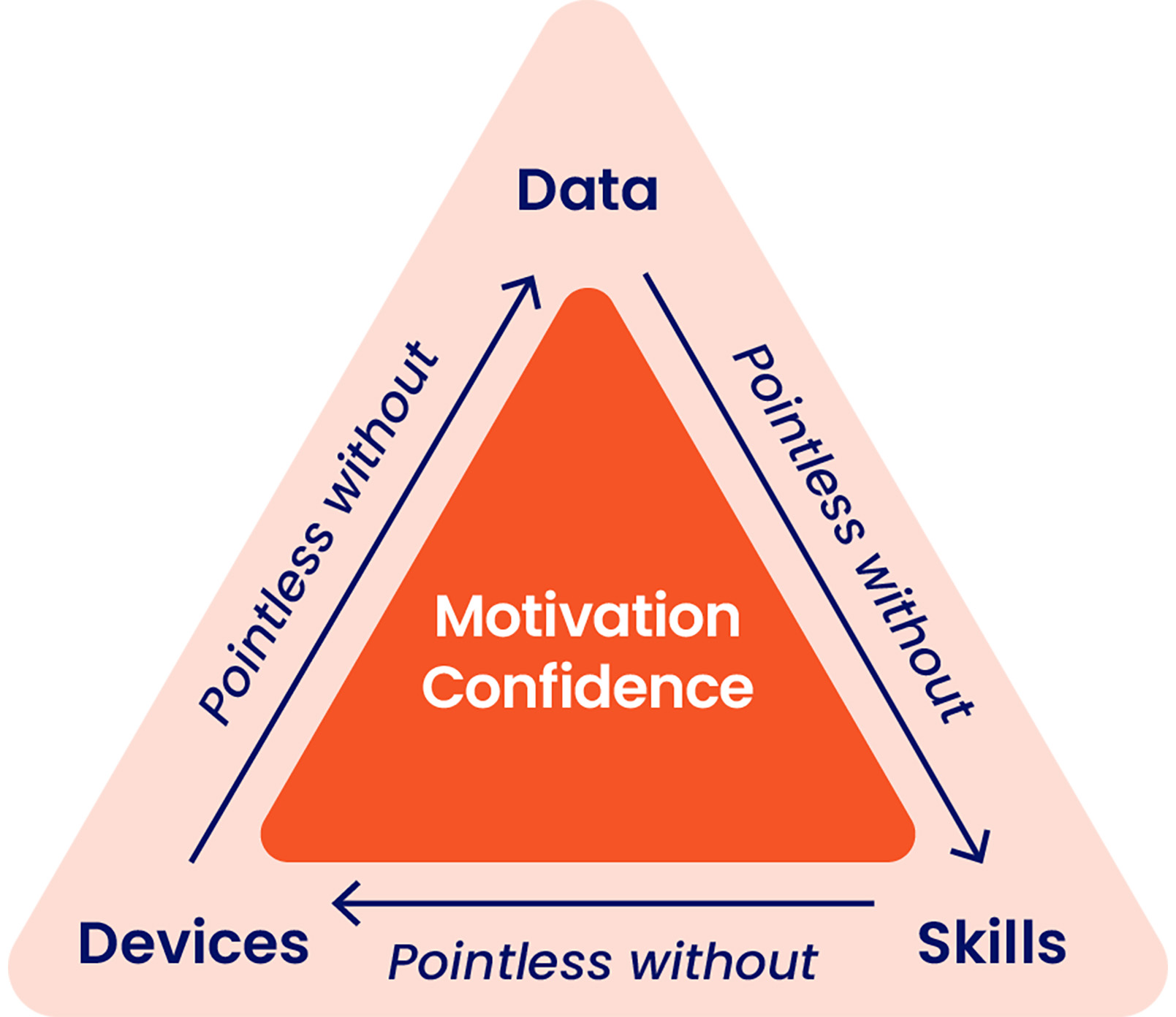

Data poverty is a key factor in digital exclusion for many individuals and households. It is, however, not the only factor. Data Poverty Lab Fellow Kat Dixon’s ‘Pointless Triangle’ highlights the importance of data connectivity and a suitable device and skills, confidence, and motivation to enable someone to be digitally included.

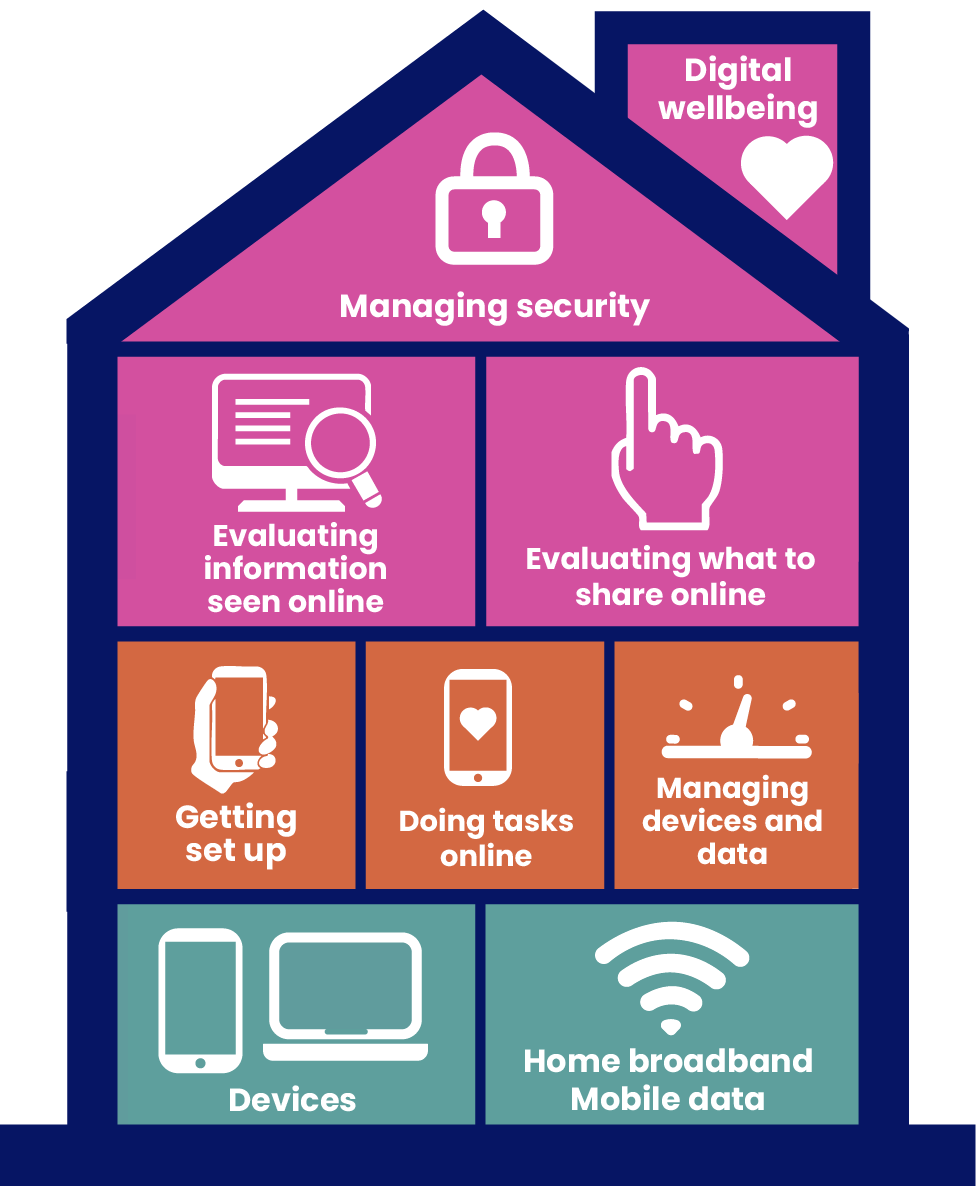

The Minimum Digital Living Standard (MDLS 2025) for UK Households is a bottom-up, holistic, household-level benchmark, developed by members of the public, to answer: what do households in the UK need today to feel digitally included. In the list of household contents, sufficient connectivity is one component of a bigger basket of digital goods and services, knowledge and skills. All are required, in combination, to feel digitally included.

.png)

Show image description Hide image description

Diagram of a house divided into rooms. Each room has an icon and text. Ground floor: Devices; Home Broadband; Mobile Data. First floor: Getting set up. Doing tasks online. Managing devices and data. Second floor: Evaluating information seen online. Evaluating what to share online. Loft space: Managing security. Chimney: Digital wellbeing.

MDLS research in 2024 identified affordability as one of the main barriers to meeting the standard for households with children. In new research, looking at needs across household types, it was challenging for groups to specify the upload or download speeds or gigabytes of mobile data. A range of principles emerged from the groups which can guide thinking.

For all households, a mix of broadband and mobile data was felt important for inclusion.

- Home broadband – with sufficient reliability and speed to support all household members to access the internet at the same time;

- Plus 5GB to 15GB per month mobile data for individuals in the household with a smartphone.

The amount of mobile data connectivity should be sufficient to cover access to essential services when out and about (e.g. maps, location apps, transport, car parking, shopping, banking, school apps) and to maintain reasonable social connection (e.g. take part in message sharing ‘in the moment’, watch or listen to short digital content but not stream or watch recurring videos. Unlimited mobile data was felt necessary for households with no home broadband. Alongside, MDLS groups said that people need the skills and knowledge to safely use free public access Wi-Fi where available; and to manage data consumption.

1.2 A changing government landscapeback to top

“The shift of government services online is a key input into the increased impact of data poverty… There’s a huge push for transformation to digital services that has lots of benefits but you can be building a massive wall between people and public services.” - P13

In January 2025, the UK Government published its Blueprint for Modern Digital Government to drive the digital transformation and reform of public services. In February 2025, the UK Government published its Digital Inclusion Action Plan: First Steps. The Government has prioritised tackling data and device poverty as one of its four focus areas.

“Data and device poverty is the inability of an individual or household to access or afford sufficient connectivity and/or a device suitable for their needs” [DSIT 2025]

The Digital Inclusion Action Plan: First Steps paper is a major step forward - and creates a window for more sustainable and systemic change. The UK Government:

- Recognises the importance of affordable connectivity for doing essential tasks

- Recognises the cost barriers especially for households on the very lowest incomes; and the importance of a good range of connectivity options to meet different needs

- Recognises that achievements, like the National Databank distributing 125,000 donated free mobile data packages, have gone unsupported by the state

- Shares pledges from industry partners to sustain their actions on affordability.

“Sufficient affordable connectivity means having access to an internet speed and data allowance sufficient for essential online activity each month. For example, applying for jobs, making appointments with your GP or maintaining contact with friends and family.” [DSIT 2025]

The UK Government has sought views on medium term proposals to address data poverty:

- Work with local authorities to consider how best to signpost existing locations where people can get online for free and explore options to expand the number of locations offering free connectivity

- Engage with Mobile Network Operators to consider how to enable easier access to government websites and online services for those in data poverty

- Explore innovative options and partnerships with housing providers, local authorities and others, to bring free or low cost connectivity to areas of high social and economic deprivation.

These proposals chime with much of the analysis and ideas in this report, while also falling short of a vision for a transformative, direct role for the Government in ending data poverty. This report offers both ideas for incremental improvements - for Government, providers, and others - as well as more radical approaches to catalyse a second wave of innovation.

Part 2: Innovations to end data povertyback to top

2.1 Four innovation areasback to top

The five years since 2020 have been a period of rising concern about data poverty - and rapid innovation and collaboration to find ways to alleviate this.

The starting point for this research was recognition that a number of innovative solutions are now in play to address data poverty. We wanted to see how they stack up against the CHESS framework - a set of principles co-created for the Data Poverty Lab with people who have lived experience of data poverty in the APLE Collective (McGrath 2022). We also wanted to explore whether they might lead to sustainable, systemic change - inspired by ‘Three Horizons’ thinking (Sharpe 2013).

We chose to explore innovations already happening, to learn what actions can be taken now to bring us closer to a future where data poverty has been solved, and point out possibilities for more radical solutions. While not our focus in this research, we see exciting potential for solutions fuelled by technical and engineering expertise, or AI and satellite technologies. A future phase of the Data Poverty Lab could catalyse collaboration and exploration with a different cohort of experts, using this report as a springboard for disruptive innovation.

The four areas of innovation we chose are:

- Social Tariffs: Discounted connectivity packages for people receiving some benefits - mainly available for home broadband, although there are some mobile social tariffs.

- Donated Mobile Data: Used in personal mobile devices (National Databank) and in providing small closed WiFi networks using special hardware (Jangala Get Boxes).

- Rochdale Mesh and OpenRoaming: Offering place-based free WiFI access for specific areas or registered users.

- Zero Rating: This enables people to use ‘zero-rated’ websites without using their data allowance; it is especially relevant to the digitalisation of public services.

2.2 Analysing innovations against the CHESS frameworkback to top

The CHESS framework was co-created with the APLE Collective (people with lived experience of poverty) in the first phase of the Data Poverty Lab (McGrath 2022). Analysing innovations against CHESS shows the need for a diversity of solutions to match the diversity of needs. Two main groups are people in urgent need, often without stable or safe housing; and people with ongoing affordability problems, such as low income families (Robinson et al 2021, MDLS 2024). How to support people to move from crisis support to long-term options (e.g. social tariffs) is hard, especially where fixed connections are not feasible. Hence the National Databank is seen both as a ‘sticking plaster’ and a ‘lifeline’.

| CHESS | Urgent Need / Crisis Support | Ongoing Need / Affordability Support |

|---|---|---|

| Cheap – Is it genuinely affordable – not just at the start but over time? | Solutions need to be free to access and not require sign up to a contract. | Contracts need to be predictable (no mid-contract rises). Costs need to be reduced through discounts. |

| Handy – Is it easy to find out about? Is it easy to apply for and access? | Solutions need to be rapidly ready to use and available through services that already support people in these groups, and are trusted by them. | Solutions need to be transparent, with clear, accessible information. Proactive promotion and automated eligibility checks reduce burdens on the user of accessing support. |

| Enough – Does it allow me to meet my essential online needs? Is it fast enough? Is there enough data? | Solutions need to provide sufficient data for individuals to engage with essential services (e.g. school, health, banking, benefits) and keep in touch with family and friends. | Solutions need to give meaningful connectivity - reliable and consistent provision, not incurring extra costs through having to purchase several or highest available products for minimal service. |

| Safe – Does it ensure my privacy is protected, and I’m not at greater risk of online harms? | Solutions need to be private to the individual, or provided through a safe and protected network. | Solutions need to support spatial privacy, for example to use online healthcare or for children to learn. |

| Suitable – Is it suitable for my circumstances, flexible if these change? Will I feel stigma or loss of pride? | Solutions need to be portable (some will not have fixed accommodation); or provided securely by local support services in different settings. | Solutions need to be stable with consistent quality of provision. |

‘[Social tariffs] have been pushed but fixed connections aren’t suitable for someone without a fixed address, for someone unhoused, a recent migrant.’ P4

The CHESS analysis also exposed consistent concerns across all innovation areas.

| CHESS | Consistent Concerns and Areas for Improvement Across Innovations |

|---|---|

| Cheap |

“It’s not cheap enough for the people most in need.” - P18

|

| Handy |

“We recognise we've got to question not just what we put in place, but the real understanding of what success looks like is that take up of that solution” - P16

|

| Enough |

“Most mobile operators are providing unlimited data plans with fair use policies. So how do we look at that from the perspective of … the Databank or … a social tariff?” - P10

|

| Safe |

“Need reassurance to trust [public wifi] is really free and to believe it's safe" - APLE Collective

|

| Suitable |

“It’s about recognising what solutions suit particular people… [and] circumstances” - P16

|

Part 3: Analysing innovations using Three Horizons Thinkingback to top

In 2022, a Data Poverty Lab long read applied ‘Three Horizons’ thinking to data poverty (Stone 2022). The ‘Three Horizons’ model was developed by Bill Sharpe as a tool for mapping possibilities for innovation and disruption relevant to social, economic and environmental change (Sharpe 2013; see also Kate Raworth’s video introduction).

Three Horizons thinking starts with defining the present – business as usual; then defining the future; and finally, exploring the potential for disruptive innovation to shape the future.

Applying this to data poverty:

- Horizon One reflects the current situation – business as usual, where data poverty and digital exclusion are still prevalent.

- Horizon Two is where we are now. Innovations already in play. Some may hold the seeds for ending data poverty (Horizon Three). Some may end up preserving the status quo (Horizon One). Horizon Two Plus is about the innovations, ideas and behaviours which can be stepping stones towards Horizon Three.

- Horizon Three is a future without data poverty; where we have the society we want, and the internet we want. We see sustainable change towards Horizon Three as a shared responsibility across industry, government, public and voluntary sectors, and individuals and households.

The ‘Three Horizons’ model encourages critical analysis of innovations in Horizon Two: will these innovations become subsumed by the structures and behaviours of Horizon One, so they end up being part of a new ‘business as usual’; or will innovations realise their potential to shift change more systemically and sustainably towards Horizon Three.

We are at an inflection point. The changing government and policy landscape opens up opportunities; the geopolitical context and tough fiscal climate constrains opportunities. The risk is that we stop pushing for Horizon Three, accepting that the innovations we have now are as good as it gets. Three Horizons gets us to look forward - look for incremental changes that can increase the positive impact of existing innovations; and look even further forward - for more radical changes that can get us even closer to ending data poverty.

In the next sections, we take stock of where the four innovation areas are now, and what we can achieve in terms of incremental and more radical changes.

3.1 Innovation Area: Social Tariffs for Broadband and Mobile Databack to top

Broadband and mobile data social tariffs are discounted products offered by some commercial providers to make home broadband services and mobile data more affordable for eligible customers. Eligibility is linked to receiving Universal Credit, or another benefit depending on the provider (e.g. Pension Credit, Pension Credit Guarantee Credit, Employment and Support Allowance, Jobseeker’s Allowance; Personal Independence Payment; Attendance Allowance). Ofcom’s website lists current social tariffs (Ofcom 2025). Broadband social tariffs are around £12.50 to £24 per month; speeds range from 15 Mbit/s to 100 Mbit/s. There are a few social tariffs for mobile data (the ‘basics’ package offered by some providers to any customer is similar to current social tariffs).

Despite being voluntary, the number of providers offering social tariffs has gone up, and products have improved. Some now offer two or three social tariffs for customer choice (faster speed for a higher price). By June 2024, social tariffs were used by over 500,000 households, or 9.6% of eligible households (Ofcom 2024). The focus has been fixed-line broadband, but 5G roll-out may make existing mobile data social tariffs more important.

Challenges

Awareness and availability are widely recognised as the main challenges, resulting in low uptake among eligible households despite clear evidence of need (Citizens Advice 2025).

- Awareness among eligible households is fairly low (31% of eligible households aware of broadband social tariffs in January 2025; Ofcom 2025). Raising awareness alone is unlikely to be sufficient to raise uptake significantly (Citizens Advice 2025).

- Availability varies depending on operator networks and coverage. Alongside pricing and product variation, this creates confusion for customers, and those signposting or supporting them, about what support is available, and where.

- There is no consistent definition of a social tariff in terms of speeds, cost, or fees to switch to a social tariff. Not all providers waive fees so people can switch to another provider’s social tariff (Citizens Advice 2025, Ofcom 2025).

Cost is a concern. Multiple reports reach similar conclusions: social tariffs cost too much for those on very low incomes, and would need to fall to £4 to £10 monthly to be affordable (Promising Trouble 2023, Tyrrell & Yates 2023; Dixon 2022; Ofcom 2022). An estimated one million eligible working-age people are in households which cannot afford a lower cost social tariff; whereas two million are in households which may not need a social tariff (Frontier Economics 2023). Reducing eligibility but improving support might be a more meaningful approach. Some have suggested removing VAT on social tariffs to reduce the cost to eligible customers (Burton 2022, VMO2 2023; Good Things Foundation policy asks 2023).

“There needs to be a review of who social tariffs are for and not for. About 8 million people are eligible, but we need to understand more granularly how it should be deployed to people who could benefit the most.” P4

“It needs to meet their own priorities, like can they access entertainment for their family.” P1

Some people in deep poverty are not ‘eligible’ for social tariffs. For example, people seeking asylum; older people on low incomes but not claiming Pension Credit (Guarantee Credit). (Only a few providers extend eligibility for their social tariffs to people on Pension Credit.)

Reports of customer satisfaction (CCP/Ofcom 2023) sit alongside customer concerns that social tariffs may be less than adequate, especially for families or households with multiple users (MDLS 2024). Offering a choice of social tariff products is a positive development, if it results in increased uptake. The application process can still be laborious, despite the collaboration between DWP and providers to streamline eligibility checks through APIs. Eligibility checks linked to benefits can also put some people off applying.

“It's very difficult to convince our service users that it's worth the pain. They have to be on the phone, they have to justify that you're on benefits … that itself is a barrier.” P8

Horizon Two Plus

Commercial providers have a responsibility to make customers aware of their social tariffs, and make it easy for people to access these with dignity. Ofcom could ask providers to report on how they are doing this, and with what success. Citizens Advice suggests a number of routes: routinely offering social tariffs at the moment of sign-up; mentioning them in every customer service call about billing or tariffs; listing them next to their other main packages online (Citizens Advice 2025).

However, raising awareness should not only be a job for commercial providers. Government and other public sector services should also build this into appropriate touchpoints with their own service users or customers, especially given the digitalisation of public services.

“Are people being informed that they can access social tariffs when they are making benefit claims? It’s those moments, those touch points, where there's an opportunity to raise awareness.” P3

DWP and Jobcentres surfaced often as an opportunity to inform people about affordable connectivity. Citizens Advice has recently called for a government advertising campaign on broadband social tariffs (the previous government ran this as part of Help for Households), and to consider Jobcentres and Universal Credit journals as a route to inform people. In taking this forward, it will be vital to learn from other schemes. One telecoms provider has worked with DWP to distribute vouchers for six months free broadband through the Flexible Support Fund; another offered 12 months free broadband for DWP customers who are disabled, carers, or receiving benefits. However, delivering these, and even securing approval for roll-out, has not been straightforward.

- DSIT, DWP, Ofcom and providers should collaborate to identify the customer touchpoints which are most effective in raising awareness among eligible individuals, and most feasible for government and commercial providers to implement. For example, DWP customer touchpoints online and in Jobcentres, and key points in a customer’s journey with a commercial provider (such as sign up and billing).

- DSIT, DWP, Ofcom and providers should pool data to explore whether tightening eligibility for social tariffs could enable a much lower-cost or free broadband package. This would reduce the quantum of beneficiaries, but could be more effective in tackling deep poverty, as well as data poverty. Unintended effects would need exploring. Extra eligibility checks could negatively impact the intended beneficiaries.

Towards Horizon Three

While mandating a single, consistent social tariff would give consistency and reduce confusion, there were concerns about whether it might lead to worse outcomes - meeting minimal obligations rather than developing products which better meet customer needs.

Social tariffs require consumers who are eligible to move to a specific product. An alternative would be for the government to fund a uniform discount (a voucher or one-off payment) for eligible customers to use with their existing provider and package of choice. This would be similar to a scheme used to address fuel poverty: the Warm Homes Discount (a one-off annual payment to eligible households, currently £150).

A ‘Connected Homes Discount’ (or similar) would offer consistency, reduce confusion, uphold customer choice, without imposing a consistent product on all providers or undermining a competitive market. It would be a way for the government to recognise internet access as an essential need, and rebalance responsibilities for tackling data poverty. It should also be easier to embed the provision of information about this in public service touchpoints like Jobcentres.

- DSIT, DWP, Ofcom and providers should do a feasibility study into a ‘Connected Homes Discount’ (or similar) which eligible households could use with the provider and package of their choice. Modelling could explore different eligibility criteria and levels of discount, based on existing data held by social tariff providers, and insights from the Warm Homes Discount, to identify the optimal balance between affordability to the public purse, to commercial providers, and to priority households.

If a statutory discount voucher scheme existed, this could open up new opportunities for the evolution of social tariff products delivered in a competitive market.

Social tariffs are not mandated. For providers and customers, the process can be laborious. What if all providers were required to deliver a basics package with the hallmarks of current social tariffs? Providers could choose whether to restrict use of their social tariffs to people receiving state benefits, or make basic packages available to all customers. Some mobile network operators already offer ‘basics’ packages open to any customer. A mandated basic broadband contract for anyone (not only benefit recipients) could be less stigmatising, and support sector-wide customer protection through a statutory alternative to disconnection. Defining what ‘basic’ means would need to be considered. With a ‘Horizon Two Plus’ lens, this could be similar to existing ‘basic’ or ‘essential’ packages. With a ‘Horizon Three’ lens, this could reflect the Minimum Digital Living Standard (MDLS 2025).

- Ofcom should commission a feasibility study and convene a ‘regulatory sandbox’ with commercial providers and others, including Ofcom Consumer Communications Panel, to explore pros and cons of mandating a ‘basic’ broadband contract for any customer. This would need to look at commercial viability; likely impact on preventing disconnection; likely effectiveness in preventing data poverty compared to targeted social tariffs; potential harms for customers on low incomes who are ineligible for social tariffs; as well as political and regulatory feasibility.

3.2 Innovation Area: SIM donation for targeted supportback to top

National Databank and Jangala Get Boxes are time-limited, targeted innovations giving free internet access through SIM donation to individuals, households, or groups of individuals. While targeted at people in data poverty, eligibility checks are not required to get support.

The National Databank is recognised nationally and internationally for its innovative offer of urgent, ‘no strings’, free mobile data for up to 12 months for adults in data poverty. Catalysed by VirginMediaO2, Good Things Foundation and Nominet, in collaboration with VodafoneUK and Three, the National Databank provides free mobile data (24GB to 40GB per month). By June 2025, over 3,600 local databanks had distributed over 266,000 mobile data packages. Delivery is currently through community hubs and libraries (National Digital Inclusion Network), some commercial outlets (O2 stores, Virgin Money stores), some public sector teams (e.g. over 40 NHS Digital Midwives in England), and several strategic place-based partners.

Jangala Get Boxes are an inspiring example of integrating innovations. Get Box hardware and software enables a single SIM to provide secure, ‘closed’ WiFi networks for up to 20 people (not all at once), who can then each access the internet. Get Boxes use donated SIMs from the National Databank. This is valuable in homes or other places where it is harder to get affordable fixed line broadband. Jangala’s model is now expanding through place-based partnerships.

Challenges

The National Databank is delivered through a network of databank hubs. It relies on donated data from O2, VodafoneUK, and Three, and goodwill of stretched voluntary and community sector (VCS) organisations. While the number of VCS databanks has grown, their availability and activity varies. Delivery has extended to the high street (O2 stores, Virgin Money stores) and some teams providing NHS or council services. There are concerns about not reaching some who could benefit; and about longer term sustainability without government support.

“It’s a brilliant offer, but you only know about it if you’ve been told. We know we have gaps in geography and in capacity… ” - S1

“It’s often informal. It’s through goodwill in the third sector.” - P1

While the opportunity to offer trust-based provision of free connectivity is greatly valued, some local VCS databanks can find the offer confusing (as donated mobile data varies by provider in terms of amount of data, length, and process involved). Also, where people don’t have an unlocked device, they may incur charges if the SIM is not compatible.

For Jangala Get Boxes, the limited amount of mobile data is the main challenge; one SIM is used in a Get Box which might support between 1 and 20 people (usually not all at once). In an evaluation of a pilot with over 400 people in temporary accommodation in Coventry, the most common request was to increase the availability of data. Limited data can also be a challenge for some Databank users depending on their situations. This relates to wider questions about what is ‘enough’ and ‘essential use’ (MDLS 2025, 2024; Dixon & Kay 2025).

“End users with unlimited data experienced greater social benefits … than those with limited data packages.” (Dixon & Kay 2025)

Horizon Two Plus

For both National Databank and Jangala Get Boxes, ongoing improvements to processes should make these innovative solutions easier for people, including delivery partners, to use. Jangala is now looking to pilot their Big Box technology in the UK to create Community WiFi hubs - an innovation which uses two SIMs with unlimited data so up to 500 people can get secure WiFi. More challenging but important to explore is what can be done to sustain the National Databank; to extend the length of time over which free mobile data is provided beyond 12 months (where people have no other option); and to extend the amount of free data donated, when used to connect multiple devices and users (recognising that it will not be commercially feasible for providers to donate unlimited data packages).

Towards Horizon Three

Time-limited free mobile data is a ‘sticking plaster’, but the National Databank has shown the need for and value of this support. A radical improvement would be to take the National Databank as a ‘proof of concept’ and, with government funding alongside industry, to support expansion across service touchpoints for people in crisis and urgent need, and who cannot use other available options. This could create a coherent, sustainable safety-net which prevents people from losing access to online services. Any organisation with a touchpoint with citizens, and a requirement for their customers to go online to access their services, should embed the Databank in their offer. Signposting and strategic integration in jobcentres and local authority one-stop shops (for example) could build on the roll-out of National Databank provision through Virgin Money stores and O2 stores.

“It might not be the priority of some of these services to address data poverty. But they need to see that it is the gateway to people accessing and making use of their services.” - APLE Collective member

“We could take the approach where there's no reason why every food bank shouldn’t be a databank. You've got the same people going in … So how do we pair that up?” - P10

The Government’s Digital Inclusion Action Plan: First Steps (DSIT 2025) recognised that the state has not supported the National Databank, and that this should change. Building on this:

- Key government departments, Good Things Foundation, National Databank’s existing industry partners, and other mobile network operators should come together to explore how government can support the National Databank to be embedded in local touchpoints where customers are in crisis or urgent need, cannot access other options, and are required to use online government or health services. Key government departments (reflecting groups experiencing crisis / urgent need) include: Department for Work and Pensions, the Home Office, the Department for Health and Social Care, and Department for Science, Innovation and Technology.

3.3 Innovation Area: Public and place based WiFi Networksback to top

Free WiFi access through specific networks is a feature of some long-established models. Eduroam has connection points for people with academic or education sign-on information; the Peoples’ Network provides free internet access for library users (Lorensbergs 2024); NHS WiFi for patients and staff in many NHS care settings. These are useful comparators for innovations like Rochdale Mesh and OpenRoaming.

Rochdale Mesh has pioneered a model of free civic wifi to reduce data poverty in deprived neighbourhoods (Rochdale Borough Council 2022). People connect to the free WiFi from their own devices using an amplified fixed broadband connection covering a local area. The council funded a three-year broadband contract. Equipment and installation costs were met by non-profit partners. The number of users depends on the reach of the broadband source. Around 4,000 devices are known to have accessed the Rochdale Mesh network.

WBA OpenRoaming is a federated Wi-Fi standard which enables seamless access to Wi-Fi for registered users across a network of Wi-Fi hotspots, managed by the Wireless Broadband Alliance (WBA 2024). Participating members pay annual fees. Pilots in the UK are underway, including with Westminster City Council as part of its digital inclusion work. The Westminster pilot already covers 300 hotspots.

Challenges

Both innovations aim to improve connectivity through localised infrastructure or seamless roaming but they serve distinct use cases and needs. OpenRoaming is a technology standard, whereas Mesh networks are a method to build networks. The success of similar models like Eduroam point to the benefits to participating organisations and users. The more challenging question is the extent to which these address data poverty, and offer a cost-effective way to tackle data poverty for public, private, and third sectors. There are also questions around safety.

WBA OpenRoaming provides safe, secure network access as long as people using the network have suitable devices, and the skills, understanding and confidence which support safe use. There is more transparency about the network (compared to other public WiFi networks), and the seamless sign-on functionality means people are not repeatedly sharing personal data across portals. However, as public WiFi networks are not always secure, WBA OpenRoaming faces a different challenge: consumer confidence. There is confusion about terms like ‘open’, ‘closed’, and ‘public’. People may lack confidence in knowing what makes a connection secure, and what to look for when deciding whether to use one. People may also lack trust in how their personal data might be used.

“If it says it’s free, is it really free? … no hidden charges and no hidden agenda?” -

APLE Collective member

Going online in a public place seldom offers the spatial privacy people need for activities such as online healthcare or banking. APLE Collective members also shared examples of people who were homeless not being allowed access to public settings to use their WiFi.

“As much as we kind of speak about all the benefits of digital hubs - at the end of the day, it's not a kind of closed private access.” - P7

Horizon Two Plus

Pilots like Rochdale Mesh and Westminster OpenRoaming may spur other local authorities to follow their lead but, in the current fiscal climate, more evidence is needed on costs and benefits before investing. Anecdotal evidence suggests that other places have attempted schemes which have stalled, but it is difficult to find lessons learned in the public domain. So the priority is for place-based pioneers and their funders to evaluate how these innovations benefit people experiencing data poverty, and what is required for safe and secure use.

- DSIT should commission research to learn from successful and stalled mesh network and OpenRoaming pilots, where tackling digital exclusion has been an aim. This should explore costs, benefits, barriers, and enablers - including what providers do, and people may need to have or know, for safe, confident use. This would give a more solid basis for future test-and-learn pilots.

- Ofcom, as the regulator for online safety, should provide guidance for providers of public WiFi networks and framework managers about what measures they need to take to ensure safety, security and data privacy for people using their services.

Towards Horizon Three

Free, secure, public WiFi might not be sufficient for the meaningful connectivity that we need today for a ‘Minimum Digital Living Standard’ - but innovations like Rochdale Mesh and OpenRoaming do open up new avenues for councils, businesses, and others to provide a different form of nationwide safety-net for internet access. Jisc has already tested connecting Eduroam to the Starlink satellite internet service (Hayman 2024).

In the future, as 5G roll-out and satellite technologies advance, the idea of a super-federated network across the UK becomes a possibility. This could connect secure networks such as Eduroam, NHS WiFi, Gov WiFi, and the People’s Network, using the WBA OpenRoaming (or similar) framework, to enable seamless and safe functionality for people to go online in local settings … as long as they have a suitable device, and the understanding, skills and confidence to benefit.

- Ofcom should do a mapping of networks (WBA OpenRoaming, People’s Network, NHS WiFi, Gov WiFi, Eduroam) against areas of deprivation and digital exclusion.

3.4 Innovation Area: Making websites free to access back to top

Zero-rating is when an internet service provider applies a price of ‘zero’ to use a website. This gives free access to their customers, so they don't have to worry about running out of data when using specific websites. In the pandemic, some providers zero-rated websites providing financial, health, and educational support for their customers. Some still do this; Virgin Media O2 applies zero-rating to over sixty websites in the UK.

Challenges

Setting aside the confusing terminology, the idea of making some websites free-to-use has generated interest. Advocates call for extending this to online public services (Clickzero). In this research, many felt that the NHS is no longer free at the point of access, with similar points made about central and local government services.

“digital exclusion is rife amongst the client base primarily in relation to access to digital services, whether that's welfare systems and such that are digital by default…” - P1

In 2023, Ofcom published its statement on net neutrality, confirming that most zero-rating would be allowed (Ofcom 2023). Ofcom opened a door for zero-rating to tackle data poverty, but it is not widely used. In this research, we had anecdotal evidence about the difficulties of applying zero-rating to NHS and Gov.UK websites, but we could not find published data on the costs or usage levels, or benefits to people in data poverty.

Horizon Two Plus

The ‘Blueprint for Modern Digital Government’ adds to the case for a look at zero-rating online public services. Without this, it is hard to make the business case (as opposed to the moral case) for public-private financing.

- Ofcom and the government should work with lived experience groups and others to explore how far data poverty would be reduced by zero-rating online public services; and the regulatory, cost, and technical barriers to using this more widely. Views could be sought on how to decide which services are zero-rated within current guidelines.

Towards Horizon Three

Zero-rating could be a systemic change in establishing a fundamental principle of providing online public services which are free at the point of access. However, while this would mitigate some of the most damaging effects of data poverty - where people are excluded from essential support - it would not enable more meaningful connectivity. A more radical vision is Tony Ageh’s proposal for a new public domain, Dot-Public (Ageh 2025). This would be a safe, online civic space, which is free to use, and provides verified public information, access to online public services, and to educational and cultural content. It would be a new ‘public service layer of the internet, governed independently and protected by law. It is designed not as a replacement for the open internet, nor as a constraint on innovation, but as a parallel civic infrastructure’ (Ageh 2025).

“Dot-Public will offer a positive alternative: a structural solution designed from the outset to serve the needs of citizens, children, families, communities, educators, researchers, and public institutions.” (Ageh 2025)

Part 4: Rebalancing Responsibility for Data Povertyback to top

One of our assumptions is that sustainable change is more likely if it is seen as a shared responsibility across industry, government, public and voluntary sectors, and individuals and households. In this section, we look at how responsibility can be rebalanced, and what else is needed to create the conditions for sustainable change:

- Government recognition that internet access is essential

- Rebalancing who pays for data poverty solutions

- Integrating different innovations in local strategies

- Government investment in evaluating costs and benefits

An overarching message is that together we can do more to end data poverty.

Government can play a more transformative role in scaling existing solutions to reach more people for more impact by integrating access to social tariffs and free mobile data into relevant public service touchpoints. This is consistent with Government ambitions for public sector reform and digital inclusion. Government should recognise internet access as an essential household need, and work with Ofom to put protections and safety-nets in place.

Local, regional and devolved nation governments can also (continue to) play a key role in catalysing, coordinating, and integrating approaches to data poverty reduction. There are existing levers and funds that local and devolved governments can use to recognise internet access as an essential need, alongside integrating a range of data poverty solutions in their place-based strategies to address poverty, and to promote digital inclusion.

Commercial providers are already backing first wave innovations such as donating free mobile data packages to the National Databank, offering discounted tariffs for broadband and mobile data, and providing free WiFi support to some local charities. They can enhance consumer protections, improve discounted products and customer support, and continue to collaborate with each other and across sectors on sustainable solutions to data poverty.

National non-profits and charities can keep on improving their services to better meet needs, advocating for change, and securing buy-in from other voluntary sector organisations and charitable funders to play their part in ending data poverty. Equipping local partners to help people move onto affordable options, and extending crisis support, are also priorities.

Local databanks and other organisations work hard to embed this into their services without specific funds. Finding ways to keep in touch with what’s available nationally and locally, and to assist people to move from crisis support to more affordable options, take time and resource but would make a more sustainable impact longer term.

4.1 Government recognition that internet access is essentialback to top

There are consistent calls on the government to recognise internet access as an essential utility or human right (see Nathaniel-Aydele 2023), with consumer protections and a stronger safety net. Often, the debate gets stuck on what would be needed to recognise internet access as a ‘fourth utility’, like water, gas, or electricity. But different levers are available.

- UK Government, Scottish Government, Welsh Government and Ofcom should use their existing range of levers, and resources to enshrine the principle that internet access is essential. The same is true of combined and local authorities.

- Enable better use of discretionary funds (e.g. Flexible Support Fund, Household Support Fund) to reduce data poverty through funding connectivity and devices.

- Use procurement levers to make internet access a requirement when commissioning support for people at high risk of data poverty, such as families living in temporary accommodation, people in dispersal accommodation, or fleeing domestic violence.

- Enhance customer protections so people are not disconnected (Sticking Plaster report). For example, by requiring providers to move people who cannot pay their bills onto a minimal service offering instead of disconnection.

- Update the Universal Service Obligation (Broadband) to reflect today’s needs (House of Lords 2023), drawing on Minimum Digital Living Standard research (MDLS 2025).

- Require registered social landlords and private sector landlords to meet internet access needs. (A proposal to amend the Renters’ Rights Bill for tenants to request Fibre to the Premises is a live example; although rejected it has put the issue on the table for future legislation, UK Parliament 2025).

- Embed understanding the requirements for connectivity, data usage, and devices into updated Government Digital Services design standards for more inclusive design.

- Ensure the Consumer Price Index and surveys used by government to define ‘essential’ household goods and services keep pace with changing realities; and add ‘digital inclusion’ indicators as a variable in population surveys.

Recognising internet access as essential can be done without legislating to make it a utility. A harder question is how much internet access is essential; and what are essential uses. Several research reports (MDLS 2024, MDLS 2025; Dixon & Kay 2025) highlight the weight we place, as members of the public, on going online for connecting with family, friends and communities, for news and entertainment, as well as to transact with services. In a world of AI, live streaming, and transition to Internet Protocol Television, our collective need for speed, reliability, and unlimited data will continue to grow.

4.2 Rebalancing who pays for data poverty solutionsback to top

All bar one of the innovations are funded by commercial and charity partnerships. Rochdale Mesh, funded through a local authority grant (supplemented by donations), does not have sustained funding beyond the initial three year grant.

Reliance on commercial providers and charities shows the power of collaborative innovation, but it also brings challenges, especially in a competitive market with relatively low broadband and mobile costs. It is time to review who pays, and rebalance the financing of solutions.

“While we [commercial providers] are part of the solution, we are not the whole solution… Data poverty is a societal and public policy challenge.” - P5

“Data poverty should be seen as the same as food poverty or fuel poverty. That means they need government priority setting and they need to resource to address them.” - P5

Government ambitions for public sector reform also raise questions about the balance of public investment in digital transformation relative to ensuring everyone can afford access. Balancing state and market contributions is a global challenge (A4AI 2021). Building Digital UK is a state-funded programme to fill infrastructure gaps; a gap remains in data poverty.

“Key government departments (NHS, DWP, etc.) gain from having a digitally enabled client base [yet] the onus has been on the ISPs to bring social tariffs closer to tenants’ affordability threshold…" (Tyrrell and Yates et al 2023)

Social Value agreements were raised as one way to better coordinate inputs across public and private sectors. National guidance was sought to make using these for digital inclusion more effective, strategic, scalable nationally, and replicable locally.

- DSIT with DWP, Ofcom, providers and consumer organisations should consider the case for introducing a state-funded discount voucher scheme for eligible DWP customers - a ‘Connected Homes Discount’. This could supplement social tariffs (or replace them if accompanied by a mandatory basic connectivity package for all).

- DSIT with Ofcom, devolved governments, providers, and relevant government departments should explore the evidence and feasibility of zero-rating online public services, starting with Gov.UK and NHS online services.

- Crown Commercial Services with DSIT should develop a framework for using Social Value agreements to drive up digital inclusion nationally, regionally, and locally.

“... local authorities have a role to play in terms of the social value - whether that's through mandating that you want a number of free connections or … x amount of laptops or … commit to the National Device Bank...” - P7

4.3 Integrating different innovations in local strategiesback to top

Data poverty responses should be integrated, not tackled in isolation. A range of nationally available connectivity options - including free connectivity, such as the National Databank - can be integrated into a holistic local strategy, alongside devices, skills, and support. This takes local leadership, coordination, communications, and relationships. There are several strong examples of integrating promotion of social tariffs and donated free SIMs into local authority digital inclusion strategies (e.g. 100% Digital Leeds, #CovConnects, Digital Essex).

Where place-based digital inclusion is effective, there are local leads who act as catalysts, convenors, and are resourceful in drawing in, and on, different sources of support:

- Convening local digital inclusion networks to bring different stakeholders together

- Using campaigns to let residents know that connectivity support is available

- Encouraging organisations to join the National Databank and be local databanks

- Using social value arrangements to negotiate connectivity benefits for local residents.

In this research, many expressed frustration at short-term funding for pilots. By contrast, permanent digital inclusion posts, backed by senior leadership, have helped put digital inclusion on a secure, strategic footing, and made it easier to attract resources into places.

“A dedicated digital inclusion coordinator role can make all the difference” (Bibby 2022)

“A lead can co-ordinate strategy, understand the eco-system around their borough, co-ordinate with community groups who provide day to day support. They can bring it together and direct resources to where there are gaps.” - P16

Localised offers of free or discounted internet services are made by major providers and also alt-nets. Targeting, uptake, and low trust (‘Where’s the catch?’) are often barriers - raising questions about how data held by councils and market providers can be better deployed. In Greater Manchester Combined Authority’s Digital Inclusion Social Housing Pilot, progress was held back by a lack of standardised wayleaves and specification across social housing, as well as outdated infrastructure in tower blocks and multi-home housing blocks (Tyrrell & Yates et al 2023).

DSIT has announced a Digital Inclusion Innovation Fund. Welsh Government is launching a grant fund for locally developed, locally delivered approaches.

- Local and combined authorities should follow existing best practice by recognising internet access as essential for residents, integrating different solutions in their local strategies, and removing barriers to providing free or discounted connectivity for priority areas and groups, such as use of standardised wayleaves agreements.

- DSIT and Welsh Government have separate plans to launch digital inclusion grant funds. This creates the opportunity to encourage and evaluate integrated approaches to tackling data poverty; and encourage funding for the voluntary and community sector - “trusted faces in local places”.

“... VCS stakeholders are often a more effective channel to some socially excluded groups than more formal council offerings” (LGA 2023)

4.4 Government investment in evaluating costs and benefitsback to top

Decision makers at all levels lack the information to decide which innovations to invest effort in, or how to most effectively expand the reach and impact of innovations operating now. As data poverty can be tackled in different ways, there is value from coordinating evaluations within a government-endorsed framework. What are the impacts of innovations relative to each other and the implementation burdens - now, and looking long term?

“If coordinated ‘test and learn’ pilots were supported and applied to local government, with rigorous evaluation from the outset for the factors that contributed to its success, learning could be shared … for faster scaling” (LGA Blueprint Response)

Minimising the burden of evaluation to the person using a data poverty solution should always feature in evaluation design. Evaluations need to respect the privacy of the end user, and minimise the cost of data collection for services (Principles for Digital Development). Innovators described how they infer impacts from aggregated usage data, limiting personal data collection.

As well as comparative cost-benefit evaluations following government guidance (Magenta Book), and drawing on existing outcome-based frameworks used to evaluation digital inclusion (such as Southby et al 2024; 100% Digital Leeds, Good Things Foundation 2025), other useful research and evaluation approaches include:

- Quantitative modelling of potential policy changes on digitally excluded groups

- Customer journey mapping with people with lived experience to identify tipping points into data poverty, touchpoints where these could be averted, and opportunities to support people to move from crisis support to more sustainable affordability support

- Market research to inform how best to build customer knowledge about data use, costs, eligibility for discounts, and safe practices when using free WiFi networks.

“It’s about recognising what's around and enhancing it and learning from it. “ - P16

Sharing lessons learned was a recurring theme. Networks like the Local Government Association’s Digital Inclusion Network in England, the Digital Inclusion Alliance Wales, and regional networks are valued places to share learning. Peer to peer learning between comparable areas with different levels of digital inclusion maturity could be worthwhile.

- DSIT and Welsh Government should work jointly and with stakeholders like the Local Government Association to develop a measurement and evaluation framework to make best use of proposed new funding for digital inclusion; and to invest in the additional expert support needed to deliver comparative cost-benefit evaluations. As well as Magenta Book principles, evaluations should be designed to minimise demands on end users and those supporting them. Participatory practice, and openly sharing lessons learned along the way, would help to widen and deepen learning.

Part 5: Conclusionback to top

Digitalisation will not stop or slow; sustained, coordinated action to end data poverty is vital.

Collaborative innovation has changed lives, shifted mindsets, and created new precedents for free and affordable connectivity. What we need to do now is maximise their impact, and sustain the drive for systemic, transformative change.

“I think that there is a sense in which industry has funded a great many initiatives and the third sector has done great work in terms of delivering, and doing the hard work of engaging with communities. I think now we just need the government to recognize it has a role to play as well. I think if government support was unlocked that would be actually transformative.” - P4

“There is an over reliance on the likes of Good Things Foundation to deliver, rather than the government saying ‘there is proof of concept, we should be running with it, or even coordinating it and plugging the gaps’. The government needs to say ‘this is our role’.” - P3

The launch of the Digital Inclusion Action Plan, Blueprint for Modern Digital Government, and AI Opportunities Action Plan makes this an excellent time for central government to take a more integral role in supporting first wave innovations and catalysing the second wave.

This report has identified actions and ideas for government, and others, to extend the benefits of innovations in play, and pursue more systemic change to prevent data poverty.

Much of this is about better use of existing levers to recognise internet access as essential, and tackle data poverty. For example, baking it into procurement of support for groups at risk, better use of existing discretionary funds, integrating crisis support, like the National Databank, into public service touchpoints, and into national and local anti-poverty strategies.

Some of this is about incremental and more radical changes to existing innovations, steering these towards the goal of ending data poverty - a mandatory basic broadband package that gives customers greater protection extent disconnection; a state-funded ‘Connected Homes Discount’ for people in data poverty, which enables customer choice and dignity.

Some of this is about being curious - exploring what it might take to scale innovations, such as zero-rating, beyond a few places or websites.

Some of this is about being more ambitious and disruptive, looking ahead to the society we want and the internet we want: a super-federated network of free and secure public WiFI; a new civic online space to access public and educational services safely and at no cost.

Through innovation and collaboration, we have already come a long way in recognising and tackling data poverty. Let’s keep going, together, and striving for Horizon Three.

“... if we come together and break the sector bubbles, we can identify solutions to each other's issues.” - P8

Referencesback to top

100% Digital Leeds et al, Digital Inclusion Toolkit: Evaluating a digital inclusion programme

Ageh, T (2025), ‘Dot-Public – a public service internet for the digital age’ (available on request, please email: tony.ageh@gmail.com)

Alliance for Affordable Internet (2021), Affordability Report 2021 A New Strategy For Universal Access. (Web Foundation)

APLE Collective (2023), The Digital Divide Briefing Paper

Bibby, W (2022), Digital Inclusion in London: A review of how digital exclusion is being tackled across London London Office of Technology and Innovation

Burton, L (2022), Reassessing VAT on broadband could generate a digital inclusion fund

CCP/Ofcom (2023), Exploring experiences with social tariffs:Research report (Jigsaw for Ofcom Communications Consumer Panel)

Clickzero, The campaign to make online public services free

Citizens Advice (2025), Barriers to Access: Why water and broadband social tariffs aren’t reaching struggling households

City of Westminster Council (2025), Access our free OpenRoaming Network

Dixon, K (2022), Scaling solutions to data poverty in the UK (Good Things Foundation / Data Poverty Lab)

Dixon, K. and Kay, E. (2025), Digital lifelines: How Wi-Fi Impacts the Lives of Residents in Temporary Accommodation An evaluation of Jangala’s Get Box Wi-Fi device in partnership with Virgin Media O2, Coventry City Council and the National Databank (Jangala)

Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (January 2025), A Blueprint for Modern Digital Government. (Policy paper)

Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (February 2025), Digital Inclusion Action Plan: First Steps (Policy paper)

Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (January 2025), AI Opportunities Action Plan (Policy paper)

Department for Work and Pensions (2024), Digital Skills, Channel Preferences and Access Needs: DWP Customers (Research undertaken by Ipsos UK)

Eduroam, What is Eduroam?

Frontier Economics (2023) Low income households and affording connectivity: Report for BT Group

Good Things Foundation, What is the National Databank?

Good Things Foundation (2025), Our approach to measuring impact of digital inclusion

Good Things Foundation with People Know How (2022), Supporting people with data connectivity (Good Things Foundation / Data Poverty Lab)

Hayman, T. “Transforming the learner experience by extending eduroam across the campus and beyond” (Jisc blog, April 2024)

House of Lords (2023), House of Lords Communications and Digital Committee: Digital Exclusion (3rd Report of Session 2022–23) HL Paper 219

Jangala, Jangala Get Box UK programme

LGA 2023 / Mack-Smith, D. (2023), The role of councils in tackling digital exclusion: A report to the Local Government Association Local Government Association

Lloyds Bank (2024). UK Consumer Digital Index 2024 (Lloyds Banking Group)

Lorensbergs (2024), Public libraries 2024

Lucas, P et al (2020), What Is Data Poverty? (Nesta and Y Lab)

MDLS 2025 / Hill, K et al (2025), A minimum digital living standard for UK households in 2025: Full report. (Available at: www.mdls.org.uk)

MDLS 2024 / Yates, S et al (2024), A minimum digital living standard for households with children: Overall findings. (Available at: www.mdls.org.uk)

McGrath, T (2022), CHESS: Co-defining what counts as a ‘good’ solution to data poverty (Good Things Foundation / Data Poverty Lab)

Nathaniel-Ayodele, S (2023), Internet Access: Essential Utility or Human Right? (Good Things Foundation / Data Poverty Lab)

Ofcom (May 2025), Social Tariffs: Cheaper Broadband and Phone Packages

Ofcom (February 2025), Communications Affordability Tracker

Ofcom (2024), Pricing trends for communications services in the UK

Ofcom (2023), Net Neutrality Review Statement

Ofcom (2022), Summary of research findings and update on availability and take-up of broadband social tariffs

Parry, B & Elliott, C (2023), Addressing data poverty for care experienced young people (Good Things Foundation / Data Poverty Lab)

Principles for Digital Development, Establish People-First Data Practices

Promising Trouble (2023), Broadband affordability estimates for the UK

Raworth, K (2018), Three Horizons Thinking: A quick video introduction (Doughnut Economics Action Lab)

Robinson, R et al ((2021), Making connections: Community-led action on data poverty (Local Trust)

Rochdale Borough Council (2022), Working Together to Bridge the Digital Gap (Co-operative Councils Innovation Network)

Sharpe, B (2013), Three Horizons: The patterning of hope (Triarchy Press)

Southby, K et al (2024), Co-producing a Theory of Change and Evaluation Framework for Local Authority-led, City-wide Digital Inclusion Programmes British Academy

Stone, E (2022), Towards Solving Data Poverty: Long read (Good Things Foundation / Data Poverty Lab)

Tyrrell, B and Yates, S et al (2023), GMCA Digital Inclusion Pilot Research Report (Greater Manchester Combined Authority and University of Liverpool)

UK Parliament (2025), Baroness Janke’s Amendment to the Renters’ Rights Bill

UNDP (2024), Digital Inclusion Playbook 2.0: From Access to Empowerment in a Dynamic World (UNDP Global Centre for Technology, Innovation and Sustainable Development)

VMO2 (2023), VirginMediaO2 steps up cost of living support for low-income households and calls for VAT cut on social tariffs

Wireland Broadband Alliance (2024), WBA OpenRoaming Introduction Guide