Learn before you try: research-led fund design

Our Head of Research, Al Mathers, talks about the importance of practice research and why it forms a large part of our work.

Why learn before you try?

Practice research has many benefits, not least because its practical nature means the benefits can be realised almost immediately – which is why it forms such a large part of our work.

For it to be as useful as possible, practice research and evaluation should be lean and look to taking an agile approach where possible. But we also need to question if we should be making all the changes along the way, once a project or programme is live. And if not, then where and when should we direct our learning?

Working for a charity – Good Things Foundation – means that we think carefully about what we fund and do. We are accountable to the lives we seek to improve through digital and the community partners we work with.

This is our approach and our culture.

But the reality is that we try things, we work with assumptions, incomplete data, and the ever-changing political and economic landscape. We do our best. Being focused on evaluating our impact, understanding what works, and what still needs investigation, refinement and iteration is how we improve

This blog is the next stage in the journey of the Research Team at Good Things Foundation, and how we’re working to ensure we are evidence-driven from the outset, so as an organisation we can make the best case for using resources at our disposal in a targeted, impactful and ethical manner.

Let me give you an example.

The Challenge

In June 2019, we launched Power Up. Power Up is a £1.3 million initiative, supported by J.P. Morgan, designed to help innovative and scalable local projects across Glasgow, Edinburgh, East London and Bournemouth to embed digital skills and approaches critical for greater economic inclusion.

The initiative focuses on amplifying the impact that a wide range of organisations can have in their communities, by taking digital inclusion into the heart of their service delivery models. For local people and small businesses with whom these organisations work, support around the informed adoption and use of digital can be transformative, propelling development of financial capabilities and employability outcomes and becoming a welcomed, valuable and utilised asset amongst small businesses who will struggle going forward without it.

So that is where we are now, but let’s rewind to September 2018 and the questions J.P. Morgan asked us that got us here:

We know digital (in the broadest sense) is important to economic prosperity, but what should we invest in to ensure greater equality of access and support? Can you tell us what that looks like? What are the gaps it will fill? What is the need it will meet? And what is the impact it will have?

Plain sailing if you’re promoting or adapting your own delivery model, but this wasn’t about us or our local partners in the Online Centres Network -this was about what should anyone do.

Hmm.

Being an investment bank, J.P. Morgan are well versed in taking an approach that mitigates risks and target funds where the greatest gains can be made. But this turned the tables on how we approached our work, as we weren’t guaranteed the investment until we could both demonstrate the need and the opportunity, and evidence this to a degree that we hadn’t previously.

Making the case wasn’t just about presenting existing and available data together as a convincing narrative. It was about interrogating below the surface of this, finding the people to talk to who could make sense of the trends we saw in data and approaching it from different perspectives. And it wasn’t a pure research exercise, otherwise I don’t think we would have had the luxury of undertaking it. It had implications for people and practice from the outset.

The Process

So we took up this challenge, and through employing different methodologies attacked it. Here are my reflections on our research process:

- Standing on the shoulders of giants: policy, practice and academia. These are all valid views that give us different perspectives created over time. We needed to hear these voices, to know the history, the shift in language, and to see what was still relevant and what might be in the future. So, we did the leg work, we read the literature and it created a foundation.

- Data is our friend: we are so lucky to live in a time where more data is created, which is accessible and freely available than ever before. Data at scale (big data) is still variable in quality and focus and needs interpretation. Having skilled data analysts in our team was a luxury, they looked across the landscape, they found the gaps, they found the people, places, and the practice.

- Data isn’t always our friend. We often found people had moved on, or data was inaccurate, so we started focusing in on practice evidence, and the reality of what we were trying to do became apparent. People are key but they move on. Names, contacts, locations all change. Organisations reinvent themselves and their practice. Survival of the fittest through evolution and adaptation may secure crucial funding, but it’s a minefield in terms of identifying what works, not replicating what doesn’t. Sustainability and continuity of practice is rarer than you think, and evidence is disjointed. This was one of our greatest challenges, creating a picture of the practice landscape when no one has this responsibility.

- Evaluation is a luxury: but surely everyone evaluates? Definitely not. The smaller your organisation, the more likely it is that evaluation is pretty low down on your list of priorities. Providing a service, meeting the needs of the next person who comes through your door, looking for funding, keeping the lights on – they are more urgent concerns. And even if you do evaluate your projects, maybe the only person who ever sees it is your funder. Writing up an evaluation for public consumption, publishing it externally, ensuring that it places you in a good light, all takes additional time, skills and resources that many organisations don’t have the capacity for.

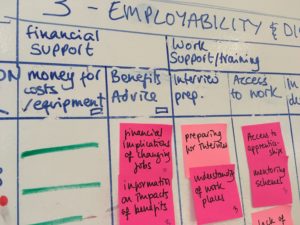

- Experts in experience: as we found, if the evidence and evaluations aren’t available you need to dig, beg and borrow. You ask people to give you their time, to point you in the right direction of others, and to broker relationships for you. We spent three months doing just this, and we learnt more than we could have hoped. We ran workshops, focus groups, face to face interviews and spoke to many, many people on the phone. We started to understand what sat below the data trends, we were able to challenge our assumptions and to see the importance of relationships, local structures, territories and legacies.

And then it began to come together, and to come together beautifully.

The Result

As a result we were able to distil our learnings into four nationally and internationally relevant reports that tackle some of the greatest challenges and opportunities around living in a digital age, and provide concrete recommendations born out of evidence and experience about how to approach these going forward.

And Power Up’s seven recommendations for national impact are powerful because of the research process we took and the challenge set us.

These recommendations are:

- Embed digital inclusion in all major initiatives for jobs and skills, financial inclusion, and small business support. Digital should be an integral component, not a ‘bolt-on’.

- Promote the benefits of the internet, especially for people on local incomes and those seeking work. Some of the biggest economic opportunities lie in motivating micro businesses and sole traders to embrace digital.

- Provide free essential digital skills support for everyone who needs it, prioritising those who are constrained by poverty. Governments at all levels need to use their devolved powers to ensure adult skills policies deliver a genuinely inclusive and effective offer.

- Support holistic approaches to digital capability that understand the wider needs of individuals, foregrounding digital skills in relation to social inclusion and education. Services should be person-centred, flexible and motivational, taking account of the interactions between individual factors, personal circumstances and external factors.

- Harness the power of peers to build skills and motivation, whether through peer support in communities or local business networks. When people share their stories of how digital has benefited them, this can motivate others.

- Encourage employers to support basic digital skills, especially for low-skilled staff, using resources available online and in communities. We need to find better ways to engage and support people in low-paid jobs, with low digital skills, who want to progress.

- Use digital inclusion to catalyse collaboration locally. Stronger strategic leadership by local authorities with comprehensive strategies for digital inclusion are needed. Co-ordinated pathways of support make it easier for people to get the support they need to progress.

Journey’s end

In July, as I travelled back from our last area event in Bournemouth discussing and promoting Power Up with people in the area, the circle felt complete. We met organisations who were new to us, and met up again with others who had been critical to our research journey. Personally, it was a pivotal moment talking with a crowded room of local experts about the research journey and findings that got us here, and the fund design that has evolved as a result.

In practice research, as I have written here, there is definitely a place to embrace agile and to learn how to be leaner. But in Bournemouth I was also proud of what we had accomplished with depth and breadth. It felt grown up, it felt important and it has delivered something we can believe in.